I wrote the same app twice, with Hotwire and Blazor Server — here’s what I learned

There’s been a very interesting movement that has emerged recently in the world of frontend web development: a rise of little-to-no-JavaScript frontend frameworks.

The promise here is that we would be able to develop web applications with rich interactive capabilities without the need to write a whole lot of JavaScript. As such, these new approaches present themselves as alternatives to the likes of Vue, React, Angular, etc.

Two recent technologies that try to fulfill this promise come from two of the most prolific web application development frameworks of today: Blazor, built on .NET, and Hotwire, built on Ruby on Rails.

Now, I love my JS frameworks as much as the next guy, but these new technologies are intriguing. So I decided to build the same application twice, with Hotwire and with Blazor. I learned a few things along the way that I would like to share in this blog post.

Note that there is a table of contents at the end of this post.

What this article is

I want to present some of my findings when working with these two technologies. I also want to discuss how they work and how they feel. How they are similar and how they are different. How they take different routes to arrive at their ultimately similar destinations. Maybe offer some pros and cons.

This post assumes sufficient familiarity with C#, ASP.NET, Ruby, Ruby on Rails and the current state of the art of web development. I won’t assume any familiarity with either Blazor or Hotwire, but this is not a tutorial for either, so I won’t explain in detail how to fully build apps with these technologies.

So who am I writing this for? Essentially, for anybody who is curious about these technologies and is interested in understanding the big picture of what they are about, how they compare to each other, and building their next project with one of them. So, this article is intended to serve more as an introduction to both, a starting point for a conversation to help you make a decision on what’s best for you and your team.

Spoiler alert: Both are great and you can’t go wrong with either. It all comes down to your team’s preferences and past experience.

One final thing worth noting is that I’m focusing this article on “Blazor Server” specifically. I’ll be using the word “Blazor” moving forward, for short. Blazor as a framework has three variants: Blazor Server, Blazor WebAssembly and Blazor Hybrid. You can learn more about them here.

Most of the examples that I’ll use in this post come from a couple of demo apps that I built in order to get my feet wet with these technologies. You can find both of them in GitHub. Here’s the Blazor one and here’s the Hotwire one. You can study both the source code and the commit history, which I tried my best to keep neatly organized. They are both functionally identical, and based on this excellent Hotwire tutorial.

An overview of Blazor

When it comes to how they are designed and the developer experience they offer, these two are very different. Let’s go over some of the key details of Blazor and then we’ll do the same with Hotwire. With that, the differences between them will become apparent.

The first thing we have to understand about Blazor is that it is a component framework, very much like Vue or React. So, with Blazor, applications are broken up into composable modules called “Razor/Blazor components” that are essentially independent pieces of GUI bundled with their corresponding logic. Each component has three parts to it:

- HTML-like markup that describes the layout and UI elements to be rendered,

- C# logic that defines the behavior of the component, like what actions to take when users interact with GUI elements, and

- CSS for styling the GUI elements.

For example here’s a simple a Blazor component that allows displaying, editing, and deleting a particular type of record called “Quote”. Don’t worry about the details too much; we’ll go over some of them next. For now, I just want us to get a sense of what Blazor components look like:

@using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore

@inject IDbContextFactory<QuoteEditorBlazor.Data.QuoteEditorContext> dbContextFactory

@if (isEditing)

{

<QuoteEditorBlazor.Shared.Quotes.Edit

QuoteToEdit="QuoteToShow"

OnCancel="HideEditForm"

/>

}

else

{

<div class="quote">

<a href="quotes/@QuoteToShow.ID">@QuoteToShow.Name</a>

<div class="quote__actions">

<a class="btn btn--light" @onclick="DeleteQuote">Delete</a>

<a class="btn btn--light" @onclick="ShowEditForm">Edit</a>

</div>

</div>

}

@code {

[Parameter]

public QuoteEditorBlazor.Models.Quote QuoteToShow { get; set; }

[Parameter]

public EventCallback OnQuoteDeleted { get; set; }

bool isEditing = false;

void ShowEditForm()

{

isEditing = true;

}

void HideEditForm()

{

isEditing = false;

}

void DeleteQuote()

{

using var context = dbContextFactory.CreateDbContext();

context.Quotes.Remove(QuoteToShow);

context.SaveChanges();

OnQuoteDeleted.InvokeAsync();

}

}

You can see that we have some C# in the file (enclosed in a @code block) with some event handlers and parameters. We also have some markup written with a mixture of HTML and C#. This markup has conditionals, wires up click event handlers, renders data from a given record, renders another component, etc. That markup is really just Razor, a templating language that has been widely used in ASP.NET for a good while now. And we also have some top-level statements like @using and @inject for including classes and objects that the component can use.

As far as CSS goes, here’s how it works: Suppose these are the contents of a file called Example.razor. The CSS for it would have to be defined in an Example.razor.css file sitting right next to it. Syntax-wise, this would just be a plain old CSS file. One cool thing to mention about it, though, is that the CSS within it is visible only to the component. So there’s no risk of conflicting rules between components.

If you’re familiar with modern frontend web development and have used frameworks like Vue or React, this should look very familiar to you. In fact, I would venture to say this is one of Blazor’s most attractive points. If you come from that background, and know .NET, it’s not that big of a leap to get into Blazor. The development experience is very similar as its design shares many concepts with modern JS frameworks; they operate under a very similar mental model.

Of course, C# is not JavaScript and .NET is not a browser. So there are many differences when it comes to the nitty-gritty mechanics of things. So a thorough understanding of the .NET framework and its libraries is also important for mastering Blazor. Which, depending on your team’s background, may be a point in favor or against.

How Blazor works under the hood

As you can probably gather from the previous discussion, Blazor takes control of the entire GUI of the application and puts up a firm layer of abstraction over traditional native web technologies. All notion of JavaScript or code executing on a browser environment is greatly de-emphasized. In fact, most of Blazor executes in the server.

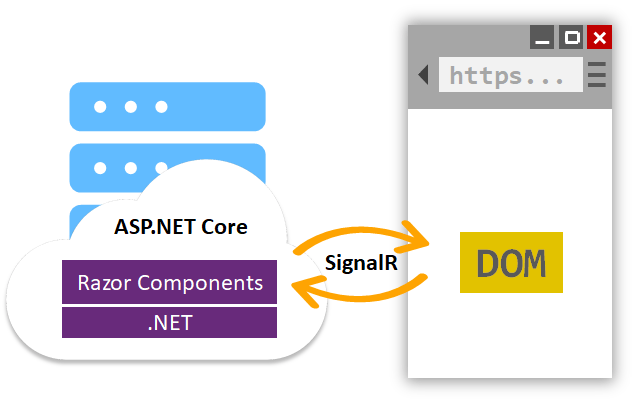

Essentially, all the code that you actually write executes on the server side. When a user begins using the app, a two-way, persistent SignalR connection is established between the browser and server. Whenever the client requests a page, the server renders it and sends it through the connection to the client browser, where there’s a component that interprets and displays it. Likewise, whenever the user interacts with some UI element, like clicking a button or a link, the action is sent to the server via this SignalR connection for it to be processed. If changes to the GUI are necessary, the server calculates them and sends them back to the user’s browser, where they will be interpreted and used to re-render the screen with the new state.

Microsoft’s official documentation has an excellent diagram that helps explain the process:

So, even though there is client side code running and browser DOM being manipulated, this is all happening under the hood. The developer doesn’t need to be concerned with that and can just focus on authoring C# code, for the most part.

This approach has a few implications worth noting. One is that this means higher load on the server compared to more traditional web applications. This is mainly because there needs to be a connection always open between clients and the server, by design. Classic HTTP is purely stateless, and connections are typically opened and closed multiple times throughout a user’s session, as they interact with the web app. Not so for Blazor, where this SignalR connection (most likely via WebSockets) is always alive. So, for scalability concerns, we need to keep in mind that the more concurrent users our app has, the more resources the server will consume, even if the users are somewhat idle.

An abstraction over the request/response cycle

A key element of Blazor is that it abstracts developers from the classic HTTP request/response model. With Blazor, one seldom has to consider that aspect, as all interactions between client and server are managed via the framework itself through the persistent connection we discussed in the last couple of paragraphs. To the developer, there’s no real separation between the two. This is a big departure from classic MVC-like frameworks where things like endpoints, actions, and controllers are front and center. Such concepts are simply not in play on Blazor apps. The idea is to make them feel more like desktop apps: fully integrated, monolithic, simple packages of GUI and functionality.

This could become a double-edged sword as, in general, it is always important to have a clear understanding of the underlying technologies that support the application stack you’re working with. That is, the web is still there, even if you can’t see it. But as long as you’re cognizant of that, this approach can have great advantages too.

For example, thanks to this approach, there’s no need to employ the classic SPA pattern of developing applications in two halves: 1. a backend Web API for domain logic written in some backend programming language, and 2. a frontend application written in JavaScript that implements the user experience and communicates with the backend over HTTP.

Blazor attempts to offer a simpler solution from a developer’s perspective, where everything lives in the same execution environment so there’s no need for inter-process communication over HTTP. The example Blazor component from before demonstrates such a case. Notice how this link has an event handler registered to its click event:

<a @onclick="DeleteQuote">Delete</a>

That DeleteQuote event handler, simply defined as the method below, directly leverages the DbContext to issue the delete command to the underlying database:

void DeleteQuote()

{

using var context = dbContextFactory.CreateDbContext();

context.Quotes.Remove(QuoteToShow);

context.SaveChanges();

}

Pretty simple.

However, this flexibility also requires great discipline from the development team. It falls upon us not to clutter the GUI code with all manner of extraneous things like database calls and domain or application logic that have nothing to do with user interface concerns. The traditional two-halves pattern for SPAs has this separation between domain and GUI logic baked in by necessity. Blazor allows us to break free from it, but that does not mean that the separation is not useful or even necessary. For a small example like this, this works just fine, but for larger applications, a more modularized design should be considered as well. Maybe the introduction of abstractions like repositories or domain services? At the end of the day, the core software design principles still need to be applied.

How Blazor supports common frontend framework features

Something else to consider, which I touched on before, is that Blazor is built on top of .NET. That means that a solid understanding of .NET concepts is all but a necessity in order to be effective with Blazor. Most of the features that are now traditional and expected in frontend JavaScript frameworks exist in Blazor, and they are implemented using age-old .NET concepts. If your team has solid .NET experience, this is a blessing. If not, then Blazor requires a larger investment, one that could be overwhelming depending on your time constraints.

Here are a few examples of how Blazor implements classic frontend framework features:

Handling DOM events

We already saw how event handlers work: they are defined as regular C# methods. The way they are registered to respond to events is via attributes in the GUI elements like @onclick or @onchange. All traditional DOM events are available. Like this:

<a @onclick="DeleteQuote">Delete</a>

Including other Blazor components

We also saw how to render components from within other components. All it takes is adding the component to the template as if it was any other GUI element/HTML tag. The tag itself is the name of the component, which sometimes needs to be fully qualified. We saw an example before:

<QuoteEditorBlazor.Shared.Quotes.Edit

QuoteToEdit="QuoteToShow"

OnCancel="HideEditForm"

/>

The fully qualified component name is QuoteEditorBlazor.Shared.Quotes.Edit in this case, and that’s how we reference it. If we were to include the namespace with an @using statement (like @using QuoteEditorBlazor.Shared.Quotes near the top of the file) then we would be able to invoke the component just by its name of Edit.

Passing parameters to components

That previous snippet also demonstrates how to pass parameters to components. In this case, we have two: QuoteToEdit which is an object, and OnCancel which is a custom event. As you can see, parameters are passed as if they were HTML element attributes. In the case of QuoteToEdit, we’re passing it QuoteToShow, which is a C# Property defined in the @code section of the component:

public QuoteEditorBlazor.Models.Quote QuoteToShow { get; set; }

In order for the receiving component to be able to accept the parameter, it needs to define a property itself of the same type, annotated with the Parameter attribute. In this case, the QuoteEditorBlazor.Shared.Quotes.Edit component defines it like this:

[Parameter]

public QuoteEditorBlazor.Models.Quote QuoteToEdit { get; set; }

Notice how the name of the property is the same name used for the “HTML attribute” that was used in markup to pass the parameter to the component:

QuoteToEdit="QuoteToShow"

In this case, the expected parameter is of type QuoteEditorBlazor.Models.Quote.

Defining, handling and triggering custom component events

The other parameter, which is a custom event, accepts a method. It looks like this in the receiving component:

[Parameter]

public EventCallback OnCancel { get; set; }

Again, this is a Property annotated with the Parameter Attribute. The only difference is that the type of this one is EventCallback. That’s what allows it to accept a method. Then, inside the receiving component, the event can be triggered with code like this:

OnCancel.InvokeAsync();

This will execute whatever method the parent component has registered as a handler for this custom event. In this case, that would be our HideEditForm method.

Handling component lifecycle events

Other than DOM and custom events, much like in other frontend frameworks, Blazor components also offer ways of hooking up to their own internal lifecycle events. OnInitialized is one of the most important ones, which runs when the component is first starting up. To hook into it and run some code when it happens, all a Blazor component has to do is implement it as a method override within its code section. Something like this:

protected override void OnInitialized()

{

// Do something here.

}

There’s more to learn about component lifecycle and the official documentation does a good job in explaining it.

Templates

Like we discussed before, Blazor also offers a rich templating syntax via Razor, which is also a hallmark of modern frontend frameworks. We have conditional rendering, support for loops, interpolation of data, model binding, etc.

Routing

Routing is also included in Blazor and the way that it works is with the @page directive that’s used on top of components like this:

@page "/quotes"

Not all components will use these, only those that correspond to whole pages. Most components will be used as portions of pages and as such, would not include these. A @page statement like the above will make the component that includes it accessible via an URL like http://mydomain.com/quotes. In other words, at the root of the site.

These routes also support parameters, which can be defined like this:

@page "/quotes/{quoteId:int}"

A component with this directive will be accessible through URLs like http://mydomain.com/quotes/123. The code in the component can access the route parameter quoteId by defining it as a Property with the matching type, annotated with the Parameter attribute. Like this:

[Parameter]

public int QuoteId { get; set; }.

State management

Global application state management à la Vuex or Redux is also available in Blazor. The cool thing about how this is implemented in Blazor is that there is no need for any additional library or special components. A global app store can be a simple C# object that’s configured to have a lifetime that spans that of the user’s session. Here’s an example of a class that’s used to store global flash messages:

namespace QuoteEditorBlazor.AppState;

public class FlashStore

{

public List<string> Messages { get; private set; } = new List<string>();

public event Action? MessagesChanged;

public async void AddMessage(string message)

{

Messages.Add(message);

MessagesChanged?.Invoke();

await Task.Delay(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(5));

Messages.Remove(message);

MessagesChanged?.Invoke();

}

}

Like I said: a plain and simple C# class. It offers a method for displaying a message for a few seconds. It does this by storing the given message into an internal variable and then, after a little while, it gets removed. It also offers a MessagesChanged event that other components can subscribe to which is triggered as messages are added and removed.

The lifetime of the instance is controlled via its dependency injection configuration. In our Program.cs, it would be configured like this:

builder.Services.AddScoped<FlashStore>();

Like I mentioned before, Blazor apps establish a persistent connection for the user throughout their session. This means that the instance of the app that is running on the server is also persistent. So, if we add FlashStore as a scoped service, one single instance of it will also persist throughout the session. That’s why we can rely on its internal variables to store global application state.

You can learn more about state management in Blazor here.

Then, you could have a component that renders those messages that looks like this:

@using QuoteEditorBlazor.AppState

@inject FlashStore flashStore

@implements IDisposable

<div class="flash">

@foreach (var message in flashStore.Messages)

{

<div class="flash__message">

@message

</div>

}

</div>

@code {

protected override void OnInitialized()

{

flashStore.MessagesChanged += StateHasChanged;

}

public void Dispose()

{

flashStore.MessagesChanged -= StateHasChanged;

}

}

Very simple too. This Blazor component uses a loop to render all the messages. There are a couple of interesting things about this one. First, the component gets access to the instance of the FlashStore class via the @inject directive near the top of the file. That’s how the flashStore variable is made available for the component to use both in C# code and in the template.

The second interesting element is how this component registers its StateHasChanged method to the MessagesChanged event defined in FlashStore. As you recall, FlashStore will trigger MessagesChanged every time messages are added or removed. By registering StateHasChanged to that event, we make sure that the component re-renders every time the messages list changes; which in turn ensures that the most current messages are always rendered. Kind of a neat trick.

And as you might expect, any piece of code throughout the app can submit new messages to FlashStore by getting hold of the global instance via dependency injection and then calling:

flashStore.AddMessage("Here's a flash message!");

Interoperability with JavaScript

For all the nice abstractions that Blazor presents us with, the reality is that sometimes we actually do have to break through them. In the case of JavaScript, this happens when, for example, we need access to some native browser feature, or when we need to integrate with some library for some widget or other type of capability. In Blazor, this is certainly possible.

There are many details to consider when it comes to JavaScript interoperability in Blazor. Check out the official documentation to learn what all is possible. For our purposes here though, it’s enough to know that calls from .NET to JS and vice versa are supported.

The most basic example of calling JS code from .NET code looks like the following. If we have a JS function like this:

window.showMessagefromServer = (message) => {

alert(`The server says: ${message}`);

return "The client says thanks!";

};

Such a method can be invoked from a Blazor component like this:

string interopResult = await js.InvokeAsync<string>("showMessagefromServer", "Have a nice day!");

The Blazor component that runs this code would have to inject an instance of IJSRuntime into the js variable with a statement like @inject IJSRuntime js. A key thing to note is that the JavaScript method needs to be attached to the window object in order for it to be accessible.

Like I said, the other way around also works: JavaScript code is able to call .NET logic defined in a server-side Blazor component. Here’s a simple example for us to get an idea of how it feels. We can have a method that looks like this on a Blazor component:

[JSInvokable]

public static Task<string> getMessageFromServer()

{

return Task.FromResult("Have a nice day!");

}

This method is public and static. It is also possible to invoke non-static instance methods, but the setup is a little more complicated, and this is enough for our purposes here. Other than that, as you can see, the method needs to be annotated with the JSInvokable attribute and return a type of Task.

Here’s some JavaScript that calls this method:

window.returnArrayAsync = () => {

DotNet.invokeMethodAsync('{YOUR APP ASSEMBLY NAME}', 'getMessageFromServer')

.then(data => {

alert(`I asked the server and it says: ${data}`);

});

};

There are a few noteworthy things here. First we have the DotNet.invokeMethodAsync function which Blazor makes available to us in JavaScript land. That’s what we use to invoke .NET server side code. Next, the function needs to be given the assembly name of our app as well as the name of the method to invoke within the Blazor component. This is the one that was annotated with JSInvokable. Finally, the function itself is asynchronous and thus returns a promise.

An overview of Hotwire

Hotwire makes a promise similar to Blazor’s. However, the way it goes about it couldn’t be more different.

Hotwire is much simpler and more minimalistic than Blazor. Whereas in Blazor we let the framework take total control of the GUI, just like we do with other popular frontend frameworks, Hotwire feels more like a natural evolution of traditional pre-JavaScript-heavy web development. We still have controllers and views, we still render pages on the server, and we still work in tandem with HTTP’s request/response model.

What Hotwire gives us, if we were to boil it down to a single sentence, is a way to refresh only portions of our pages as a result of user interactions. That is, we’re not forced to reload the entire page, as is the case with non-JavaScript web applications. For example, in Hotwire we have the ability to submit a form or click a link and, as a result of that, only update a particular message, picture, or section.

ASP.NET veterans will find this awfully familiar. That’s because all the way back in version 3.5, ASP.NET AJAX offered a very similar feature: partial page updates with the UpdatePanel component. Indeed, Hotwire presents a very similar concept; only greatly improved and modernized.

When it comes to actual coding, Hotwire’s footprint is minimal. It augments traditional Ruby on Rails controllers and views to produce the desired effect of page refreshes that are partial and targeted. Let’s walk through an example and you’ll see how we can start with a regular looking Rails app and then, through minor adjustments, we end up with a more richly interactive experience.

Imagine we are beginning to develop support for CRUDing a particular type of record called “Quote”, and we have these files:

### app/controllers/quotes_controller.rb

class QuotesController < ApplicationController

def index

end

def new

@quote = Quote.new

end

end

<!-- app/views/quotes/index.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<div class="header">

<h1>Quotes</h1>

<%= link_to "New quote", new_quote_path %>

</div>

</main>

<!-- app/views/quotes/new.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<%= link_to "Back to quotes", quotes_path %>

<div class="header">

<h1>New quote</h1>

</div>

<%= render "form", quote: @quote %>

</main>

<!-- app/views/quotes/_form.html.erb -->

<%= simple_form_for quote do |f| %>

<% if quote.errors.any? %>

<div class="error-message">

<%= quote.errors.full_messages.to_sentence.capitalize %>

</div>

<% end %>

<%= f.input :name %>

<%= f.submit %>

<% end %>

This sample is using the

simple_formgem, which you can learn more about here.

If you’re familiar with Rails, then you understand what’s happening here. We have a simple index page with a heading and a link to another page. That other page contains a form to create new Quote records. It also contains a link to go back to the index page.

Partial page updates with Turbo Frames

As they are right now, these files would produce a traditional web application user experience. When links are clicked, the whole screen will be reloaded to show the page that the clicked link points to. But what if we wanted, for example, to have the new record creation form appear out of nowhere within the same index page, without a full page reload? Here’s what that would look like with Hotwire:

<!-- app/views/quotes/index.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<div class="header">

<h1>Quotes</h1>

<%= link_to "New quote",

new_quote_path,

+ data: { turbo_frame: dom_id(Quote.new) } %>

</div>

+ <%= turbo_frame_tag Quote.new %>

</main>

<!-- app/views/quotes/new.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<%= link_to sanitize("← Back to quotes"), quotes_path %>

<div class="header">

<h1>New quote</h1>

</div>

+ <%= turbo_frame_tag Quote.new do %>

<%= render "form", quote: @quote %>

+ <% end %>

</main>

Remember that these examples are taken from a fully working application. Feel free to read through the source code to have a more complete understanding of the context within which these files exist.

And that’s really all it takes. Let’s go over it. With these changes, whenever a user clicks on the “New quote” link, instead of the browser triggering the usual GET request to then reload the screen and show the creation page, Hotwire’s frontend component captures the click event and makes the request itself via XHR. The server then receives this request normally and routes it to the new action in the quotes controller. All that action does is render the new.html.erb template and send that back to the client as a response.

When the Hotwire frontend component receives this, it notices that some of the response is enclosed in a turbo_frame_tag whose ID is that of an empty new Quote object. Now, because the link that the user clicked also had the ID of an empty new Quote object as its data-turbo_frame attribute, Hotwire looks for a turbo_frame_tag with the same ID in the page that’s currently being shown an replaces its contents with the contents from the similarly named turbo_frame_tag from the incoming response.

With that, you’ve seen in action some of the key elements that make Hotwire work. First of all we have the turbo_frame_tag helper, which produces a so-called “Turbo Frame”. Turbo Frames are the main building block that we use for partial page updates. Turbo Frames essentially say: “This section of the page is allowed to be dynamically updated without a full page refresh.” In an app that uses Hotwire, whenever you’re in a page that includes a Turbo Frame, if a request is made (whether it be navigation or form submission), and if the resulting response includes within it another Turbo Frame with the same ID, then Hotwire will notice the match and update the current page’s Turbo Frame with the contents of the Turbo Frame from the response.

Looking back at the code, you can see how we achieved this. We added an empty Turbo Frame on the index page, right below the link to the creation page. We also wrapped the form from the creation page in a similarly named Turbo Frame. Finally, we added the data-turbo_frame attribute to the link in the index page to tell Hotwire that it should kick in for this link and target that specific Turbo Frame. If the link was inside the Turbo Frame, we would not have to do this. Since it is outside, Hotwire needs the little hint that says: “Treat this link as if it was inside this Turbo Frame.”

I feel like this is at the same time a little awkward to wrap your head around and deceptively simple. When compared to Blazor, which builds upon tried and true concepts (as far as the developer experience goes at least), Hotwire almost seems alien, with a much more unusual style. But all in all, one can’t deny just how clean and simple all of this looks, in that “Rails magic” kind of way. And once it clicks, you can begin to see a world of possibilities opening up. The Hotwire developers managed to identify and extract a general design pattern of web application interactions, one that can be leveraged to produce a lot of varying rich interactive user experiences.

One neat aspect worth noting is that, if the user were to disable JavaScript, the app would still fully work. It would gracefully degrade. This is a direct consequence of Hotwire’s paradigm of adding minimal features on top of the existing traditional Rails programming model.

Imperative rendering with Turbo Streams

Let’s consider another example now. This time we’ll see another key component of Hotwire in action which is called Turbo Streams.

Turbo Streams helps solve the problem that emerges when the declarative style of pure Turbo Frames is not enough to obtain the fine grained control and behavior that we need. In these cases, the server needs to issue specific commands to the frontend on how to update the GUI. Via Turbo Streams, we can achieve just that. Coding-wise, these look like regular Rails view templates, albeit with some funky syntax thanks to the Turbo Stream helpers.

In our example, we’ll add a list of quotes in the index page, right below the link and the form. We’ll also complete our quote creation implementation so that we’re actually able to submit the form. As a result of that, we want the GUI to be updated so that the form goes away and the newly created quote is shown in the list. These last two are the things that we’ll use Turbo Streams for. Of course, these updates to the page will be done without a full page refresh.

Let’s start by adding a list of quotes on the index page.

In the controller, we query the database for all the quote records and store them in a variable that the view can later access.

### app/controllers/quotes_controller.rb

class QuotesController < ApplicationController

def index

+ @quotes = Quote.all

end

def new

@quote = Quote.new

end

end

In the index view template, we render the collection of records.

<!-- app/views/quotes/index.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<div class="header">

<h1>Quotes</h1>

<%= link_to "New quote",

new_quote_path,

data: { turbo_frame: dom_id(Quote.new) } %>

</div>

<%= turbo_frame_tag Quote.new %>

+ <%= render @quotes %>

</main>

Now we need to define a “_quote” partial view so that render statement we added on the index view can work automagically.

<!-- app/views/quotes/_quote.html.erb -->

<div class="quote">

<%= quote.name %>

</div>

With this, the render @quotes statement will loop through all the records in @quotes and render this partial view for each on of them. This template is very simple. All it does is render the name of the quote.

Now let’s add an action that can accept quote creation form submissions:

### app/controllers/quotes_controller.rb

class QuotesController < ApplicationController

def index

@quotes = Quote.all

end

def new

@quote = Quote.new

end

+

+ def create

+ @quote = Quote.new(quote_params)

+

+ if @quote.save

+ redirect_to quotes_path, notice: "Quote was successfully created."

+ else

+ render :new

+ end

+ end

+

+ def quote_params

+ params.require(:quote).permit(:name)

+ end

end

A typical Rails recipe for a record creation endpoint. It takes the parameters coming from the request and uses them to create a new record via the Quote Active Record model. If successful, it redirects to the index page; if not, it renders the creation page again (via the new action). The new.html.erb view template has some logic to render error messages when they are present so those are going to show up when that page is rendered as a result of unsuccessful calls to this create endpoint.

At this point, we’re able to view all the quotes on record and create new ones. Now here are the changes to Hotwire-ify this scenario.

First we wrap the list of quotes with a Turbo Frame named “quotes”:

<!-- app/views/quotes/index.html.erb -->

<main class="container">

<div class="header">

<h1>Quotes</h1>

<%= link_to "New quote",

new_quote_path,

data: { turbo_frame: dom_id(Quote.new) } %>

</div>

<%= turbo_frame_tag Quote.new %>

+ <%= turbo_frame_tag "quotes" do %>

<%= render @quotes %>

+ <% end %>

</main>

Next, we employ Turbo Streams. Like I said, Turbo Streams materialize themselves in code as if they were view templates. So, a new file is added that looks like this:

<!-- app/views/quotes/create.turbo_stream.erb -->

<%= turbo_stream.prepend "quotes", partial: "quotes/quote", locals: { quote: @quote } %>

<%= turbo_stream.update Quote.new, "" %>

It sort of looks like a couple of imperative statements, does it not? The first line instructs Hotwire to prepend, in the "quotes" Turbo Frame, a new render of the app/views/quotes/_quote.html.erb partial view, while passing it the @quote object as a parameter. The second line updates the Quote.new Turbo Frame to be empty. When we remember that the "quotes" Turbo Frame is the one that contains the list of records and the Quote.new Turbo Frame is the one that contains the new quote creation form, this starts to make sense. This Turbo Streams view is making the newly created quote appear in the list; and at the same time, it is making the form disappear. From a user’s perspective, this all takes place after submitting the creation form. So the user experience makes complete sense. All that with no full page refresh.

And finally, the controller action needs to make use of this new view template like so:

### app/controllers/quotes_controller.rb

def create

@quote = Quote.new(quote_params)

if @quote.save

- redirect_to quotes_path, notice: "Quote was successfully created."

+ respond_to do |format|

+ format.html { redirect_to quotes_path, notice: "Quote was successfully created." }

+ format.turbo_stream

+ end

else

render :new, status: :unprocessable_entity

end

end

This is yet another familiar Rails pattern. This is how we specify different response formats, whether it be HTML, JSON, XML. Now, thanks to Hotwire, we can also specify Turbo Streams. This is one of the great aspects about Hotwire: it seamlessly integrates with Rails’ existing features and concepts.

Anyway, in this case, we invoke format.turbo_stream within the block passed to respond_to and that makes it so the app/views/quotes/create.turbo_stream.erb view template is included in this action’s response. Hotwire’s frontend component sees this coming as part of the response and acts accordingly, updating the GUI how it’s been specified.

Adding JavaScript with Stimulus

The final piece of the Hotwire puzzle is Stimulus, which allows us to integrate JavaScript functionality in a neat way. Stimulus is a very simple JavaScript framework, it does not take control of the entire UI. In fact, it does not render any HTML at all. Stimulus essentially offers a nice way of wiring up JS behavior to existing markup. Let’s look at a quick example of how it could hypothetically be used for showing a confirmation popup before deleting a record.

The JavaScript logic lives inside so-called “Stimulus controllers”. For our example, it could look something like this:

// app/javascript/controllers/confirmations_controller.js

import { Controller } from "@hotwired/stimulus"

export default class extends Controller {

confirm() {

if (confirm("Are you sure you want to delete this record?")) {

// Carry on with the operation...

}

}

}

And now, the idea is to wire up this code so that it runs when the hypothetical delete button is clicked. Here’s what that button could like:

<button

data-controller="confirmations"

data-action="click->confirmations#confirm"

>

Delete

</button>

Pretty self-explanatory. We specify the name of the controller to use via the data-controller attribute. We also specify, via data-action, what method to invoke within that controller as a result of which DOM event, click in this case.

And that’s basically all it takes to sprinkle some JavaScript on Hotwire apps. Stimulus does offer a few more useful features, which you can read more about in the official documentation. But for us for now, it’s enough to know that it exists, and what’s the main idea behind it.

So as you can hopefully see, Hotwire is much smaller in scope to Blazor. And yet, it allows us to do just the same: highly interactive applications with little to no JavaScript. This ought to make a lot of Rails developers happy.

A final comparison

I was initially thinking about ending this blog post with a flowchart of sorts to explain the process of deciding which of these two technologies you should use. But really, the decision is very simple: If your team is comfortable with .NET, use Blazor. If your team is comfortable with Ruby on Rails, use Hotwire. It’s obvious, so I won’t claim to have made a great discovery here.

The only thing to add is that if your team is familiar with modern frontend web development framework concepts, you’ll be even better served by Blazor and you’ll hit the ground running. If not, then even for seasoned .NET people, there will be a decent learning curve, but not steep enough to be deterred. Moreover, if your team has no modern frontend development experience at all, then Hotwire is a godsend; thanks to its “augment classic backend-heavy web app development” style.

With that said, let’s close out with a summary of main aspects of both technologies and how they compare to each other.

Overall, Hotwire is much simpler than Blazor. While Blazor is a full-fledged GUI component framework, Hotwire’s approach is more like an augmentation of classic non-JavaScript web development patterns. That said, Hotwire’s style is more unusual than Blazor’s, so if your team is already familiar with modern frontend web development, Blazor can be a great fit.

While both frameworks try to offer enough functionality to allow the development of rich interactive experiences without the need to write any JavaScript, the reality is that sometimes JavaScript does need to be written. Both technologies offer ways to make this happen. And while both are perfectly workable, Blazor’s solution is a bit more clunky than Hotwire’s.

When it comes to classic web technologies like HTTP’s request/response cycle and the separation between server and client, Blazor’s style offers a big deviation from them. It greatly de-emphasizes them and presents instead a completely different programming model, one more akin to desktop application development. The concepts of request, response, client, and server seem to vanish. Not so for Hotwire, which builds upon these classic technologies in a way where they still need to be considered and are in fact in the spotlight. While Blazor attempts to do away with these, Hotwire embraces them.

In Blazor, client events are sent to the server, the server renders the DOM updates and sends them to the client for updates. This happens via the persistent SignalR/WebSockets connection.

Hotwire, on the other hand, intercepts client events and sends classic HTTP requests (via AJAX/XHR) to the server. The server then executes the requests and sends back the responses to the client which carries out the necessary operations, generally speaking, updating sections of the page that’s already being displayed.

That means that at the end of the day, both frameworks do the rendering on the server side and send the rendered markup over the wire to the clients. But in Blazor, the client and server have a persistent connection, while Hotwire’s connections come and go as normal HTTP requests and responses.

A neat aspect of Hotwire’s programming model is that it allows an incremental approach to web development where you can start developing the app like you would a traditional, non-reactive, non-JS app, then augment it with a little code to give it SPA capabilities.

And that’s all for now! I for one am glad to see these types of technologies emerge. While there are many teams out there that are already effective and productive with the current landscape of frontend web development, these two are very interesting and seem capable in their own right.

Besides, having alternatives is never a bad thing. Depending mainly on your previous experience, these could be a great fit for projects new and old. It’s great to know that both .NET and Rails include these types of offerings and that they work pretty well.

Table of contents

- What this article is

- An overview of Blazor

- An overview of Hotwire

- A final comparison

frameworks ruby rails csharp dotnet aspdotnet

Comments